Pain

A normal reaction to a stimulus by the body is pain. This is the method of communication that something is irritating the body and should be corrected. Sometimes the body responds automatically before pain is severe such as feeling heat. The body immediately removes itself from the stimulus. At other times, pain is noticed as something bothersome that needs to be fixed like an itch or something is too tight. Still, in other events, pain is a warning of a catastrophic event in the body such as a heart attack or broken bone.

Reactions to pain are different for everyone. This is because of cultural issues, conditioning, tolerance, genetics, as well as other social and physiological effects. Some individuals have been taught to tolerate pain by becoming stoic while others have extreme pain issues that others would just ignore. The responses to pain are unique to each person. No two people will have exactly the same pain experience or response to pain treatment.

The pain process in the body consists of four components.

- Transduction is the sensation of pain in the tissue.

- Transmission is sending the message of pain to the brain.

- Modulation is the ability to reduce transmission activity.

- Perception is the awareness of the sensory signal.

In neurological trauma or disease, any part or all of the four components of the pain process can be affected. You may not feel pain (transduction), the message may not be able to be sent to the brain (transmission), the brain may not be able to respond (modulation), or you may not have the ability to notice pain (perception).

Pain duration is classified as acute or chronic.

Acute pain is temporary. It begins with an irritation or problem and generally resolves with the healing or correction of that problem. Most often acute pain lasts less than six months, typically much less. Temporary use of pain medication may be needed. Examples of acute pain may include a stubbed toe, a cut, a broken bone, or tooth pain, among others.

Chronic pain may begin as an acute pain that does not resolve or is pain that occurs over months or years. It can be intermittent or continuous. Medication is typically used for long-term treatment as well as other therapies. Usually, chronic pain occurs from ongoing health conditions such as arthritis, neurological diseases or injury, or damage or changes in nerves, among other issues.

Types of pain include:

Emotional pain is a physiological response to events in life that affect mental health. These types of events may include rejection from others, grief, loss, depression, anxiety, regret, rage, hate, or any feelings of remorsefulness or exclusion. Long-term physical pain can also lead to the creation of emotional pain.

Emotional pain particularly affects the parts of the brain called the anterior insula (responsible for executive control of emotions) and the anterior cingulate cortex (responsible for thinking, motivation, decision-making, conflict, and social cognition). These are parts of the brain that work together to maintain emotional stability. Unpleasant issues can upset the natural balance of function, especially in these parts of the brain. The results can be temporary or long-term.

As all parts of the body are interconnected, emotions or feelings can affect physical function. A simple example of emotional pain affecting body functions is getting so upset at something that you want to throw up or have diarrhea when anxious. Some individuals with depression are unaware of their emotional issues but have physical manifestations such as difficulty with joint pain, physical issues with getting up out of bed, decreased appetite, and other physical issues.

Nociceptive pain occurs within the body. This pain is from injury to skin, muscles, joints, tendons, and bones. It is usually described as achy or throbbing pain. Sensory receptors in all parts of the body, both internally and externally, send a message to the thalamus and cortex of the brain that triggers a response. It may be to move a body part for comfort, blood flow, or even an itch. More severe nociceptive pain may indicate you need medical attention.

Some particular types of nociceptive pain have specific names. These include:

- Musculoskeletal which is pain in the muscles and bones.

- Visceral is pain specifically in the organs of the body. Examples are surgical pain or internal health issues such as gallbladder attack or bowel impaction.

- Ischemic pain results from a lack of blood flow to the organs of the body. Examples are heart attack or peripheral vascular disease.

- Referred pain occurs when pain in one location or body organ is felt in another part of the body. The most commonly known referred pain is in the left shoulder or jaw with cardiac issues such as heart attack. Referred pain after paralysis occurs most often in either shoulder or side of the jaw but can be felt anywhere especially if there are alterations in sensation in parts of the body.

- Zone of Transition pain is sometimes seen in individuals with paralysis. The muscles above where sensation is felt are required to do some of the work that muscles below the level of injury cannot perform. This creates muscular pain until tolerance is built.

There are many occasions when nociceptive pain and neuropathy pain are found in combination. One example is dental pain originating from the teeth as with a cavity, impaction, or extraction. It can consist of muscular and nerve pain. However, since it can be treated with dental care, it is not considered to be chronic neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain is a miscommunication of messages by the nerves. The source of neuropathic pain can be in the nerve itself, in the transmission of messages through the spinal cord, or in the perception of the message in the brain as in spinal cord injury and disease and brain injury. Neuropathic pain is usually described as electrical jolts or burning. This pain is typically chronic. It can be intermittent pain events or continuous.

Neuropathic pain can develop from some health conditions. There are specific types of neuropathic pain:

- Alcoholism and drug overuse can create neuropathy and neuropathic pain from overconsumption.

- Diabetic neuropathy is pain from the result of nerve damage due to lack of blood flow as a consequence of diabetes.

- Radicular pain is a particular type of neuropathic pain which is a compression of a spinal nerve or nerve root usually in the leg leading to sciatica.

- Phantom pain is particular to individuals who have had an amputation of a body part but still feel pain in the absent body area. It stems from the nerve endings close to the point of amputation wanting to continue to send or receive messages. On rare occasions, individuals with head injury or spinal cord injury may feel pain in the part of the body that is affected by paralysis. This is not true phantom pain because the limb is still there but a similar type of experience. In this case, the event is neuropathic pain.

Nocioplastic pain or Inflammatory pain is ongoing or continuous nerve and tissue damage typically from internal inflammation. It is a progressive pain as the nerve and tissue become further damaged. Typically, it occurs in neurological diseases such as fibromyalgia and may be present in tension headaches, and back pain. It also occurs in rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

Symptoms/Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pain can be challenging especially if there are issues with sensation. The pain experience may not be able to be pinpointed on the body or described in usual terminology. It may not be recognized for its true severity. Pain experiences with decreased or absent sensation can range from fuzzy to extreme but it still is a significant issue for the person who has it.

Children might not have the vocabulary to describe their pain, individuals with aphasia may not be able to relate pain symptoms, and those with spinal cord injury may have difficulty determining the source of pain. It is critical to keep working with your healthcare professional to establish the source and type of pain to get the treatment you need. This is not unusual. Pain diagnosis is a process.

A healthcare provider will need the following information to make a pain assessment:

– A full general health history.

– A complete history of neurological issues. This will help direct the discussion. An ASIA exam for individuals with spinal cord issues and a neurological exam should be performed for everyone with neurological issues.

– The history of your pain, including:

- When the pain started, if known, and how it has progressed.

- Where the pain starts in the body and if it travels through the body.

- When the pain occurs, if the pain resolves and comes back, is the pain affected by activity, change in position, weather effects, or other events.

- Everything you have been doing to help your pain including how effective these treatments have been. This might include over-the-counter medications and ointments, prescription medications, recreational drugs and oils, exercise, immobilization, elevation, foods, how the pain affects sleep, and anything else you have tried.

– Words to describe your pain:

Sometimes finding the exact word or words to describe you pain can be difficult. Click here for a list of commonly used words to describe pain.

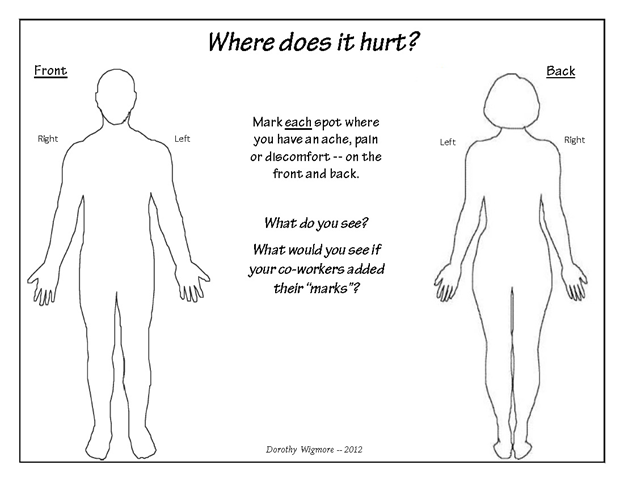

– A body pain map can be used to identify the areas where your pain is felt. This should be a representation of where you feel pain, although it may not be where your pain is or has occurred due to altered sensation from neurological disease or injury. It does provide guidance to the healthcare provider as they may see a nerve pathway or referred pain from a particular area. Indicate your pain with an X, a dot, a huge circle, a shaded area, or different colors for intensities.

Graphic Credit for “Where does it hurt?”: Body Mapping from Wigmorising

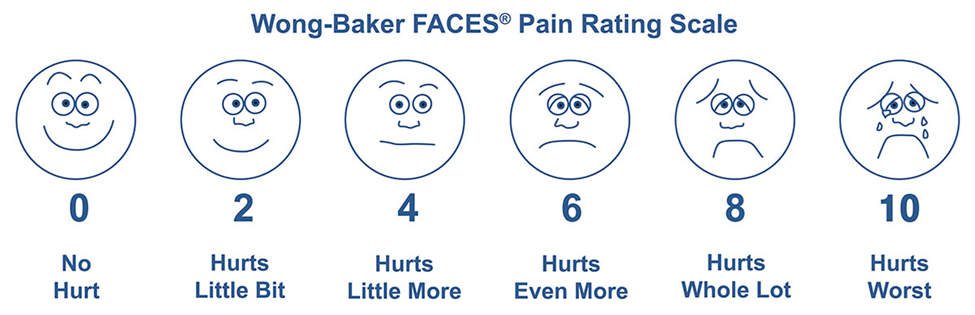

-A pain scale assessment. Typically, a scale of 0-10 is used with 0 being no pain up to 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable. Children, those who are unable to speak, or those who do not communicate in English may use the FACES scale:

Graphic Credit for Pain Rating Scale: Wong-Baker FACES Foundation

– A pain diary is a helpful chronicle of your pain, the intensity, when it begins, what you are doing when you have the pain, what you did to control the pain, and if it stops.

– Imaging studies and testing may be performed to assist with the diagnosis of pain. These may include:

- X-rays view body placements and displacements of organs and bones

- CT Scans (Computed Tomography) create images of bones, organs, and soft tissue

- MRI (Magnetic resonance imaging) displays internal images and some functions of the body

- EMG (electromyogram) is an electrical test of muscle function

- NCS (nerve conduction test) is an electrical test of nerve function

- Grip function is an assessment of hand gripping power using a hand-held dynamometer

- Manual measurements of the strength of other parts of your body may be assessed

Treatment

The treatment of pain is based on the type of pain you are experiencing. For example, treatment of muscular pain will control neuropathic pain. Therefore, the diagnosis of your pain is important.

For any type of pain, some general interventions are:

Gentle movement. The body wants and craves movement. Fast, jerky movement can increase pain but slow, gentle movement can reduce pain. If you have difficulty moving your body, have someone gently move it for you.

Aquatic therapy. Water adds buoyancy, reducing the effects of gravity, to help support the body and extremities. Warm water pools work well as the warmth relaxes muscles whereas cold water contracts muscles making movement more difficult and often more painful.

A healthy diet and drinking water. Eating a healthy diet provides nutrients your body needs for healing. Fluid hydrates the body to keep tissues healthy and joints fluid. For those who maintain a bladder program, be sure to stay within your fluid limits.

Therapeutic treatment for pain may include physical therapy for stretching and strengthening joints and muscles.

Emotional pain is often felt with physical symptoms, however, getting to the root of the emotional pain is needed. Many individuals will begin with treatment for their physical symptoms, if present, but do not find relief until the emotional issue is treated. In fact, not being able to get physical symptom relief is one of the first signs that the issue could be emotional. A psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist can assist with helping you to identify your concerns and work with you for treatment.

Recognition of your emotional pain is a first step. Most individuals will need some professional assistance in learning strategies to treat their mental health. This can be done with a therapist, counselor, religious leader, or psychologist. Family members may need to participate as well if that is the right treatment for you.

Some types of therapy may include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) which assists with seeing a challenging issue and strategies to deal with it. CBT is often used in post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Psychotherapy where you talk about your thoughts and feelings with a professional

- Problem-solving therapy which may be done in a group with others to learn how they are dealing with the same issue or loss.

Medication may be needed to treat anxiety, depression, or other mental health issues. These may include:

- Antidepressants are used for a variety of mental health issues. These may include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Antipsychotics (neuroleptics) are prescribed for neuropsychiatric conditions such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, dementia, depression, eating disorders, personality disorder, insomnia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder as well as other issues.

- Mood stabilizers help regulate extreme mood shifts.

Treatments for more advanced emotional pain include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), light therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Strategies for helping yourself with emotional pain can be done by anyone. These activities include:

- Spending time with others, reducing isolation

- Participating in an activity you enjoy

- Exercising your body or having someone move your body for you

- Journaling your thoughts and concerns

- Practicing mediation or mindfulness

Some individuals who experience emotional pain respond to treatment immediately while others take more time. This does not mean your condition is less or worse, it is just an individual body’s natural response to treatments. Responding to any treatment may take more time for some individuals.

Interestingly, the same medications used to treat emotional pain are used in lower doses for the treatment of tone/spasticity. Therefore, some individuals in treatment for emotional pain may have little tone/spasticity issues.

If you find yourself in desperate need of help for your emotional pain, contact your primary healthcare provider or call 911. Available in the United Staes is a mental health hotline that can be called or texted at 988.

Nociceptive pain treatment is directed to the reduction of pain symptoms at the source. A medical cause of nociceptive pain should be addressed to reduce the pain as well as to decrease the continuation of pain. Underlying medical issues requiring treatment should be addressed such as treatment for medical conditions such as alcoholism, diabetes, heart disease, or other health issues. Surgery may be needed to correct some internal issues.

Specific sources of nociceptive pain in neurological issues may include treatment for tone/spasticity which may reduce pain. Therapeutic exercises for strengthening as well as positioning equipment will assist with muscle aches at the zone of transition between working muscles and less responsive muscles.

Most often, over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen, or other mild analgesics are provided. Ibuprofen or other anti-inflammatory medication is used to reduce swelling in the area. These medications must be taken as directed to avoid side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding or kidney failure. In severe cases of nociceptive pain, prescription medications may be taken for a limited time. Low-dose antidepressants might be used for the side effect of reducing pain. Opioids are not recommended due to their addictive properties.

Neuropathic pain and Nocioplastic pain which arises from nerve miscommunication or inflammation is generally not responsive to anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications. In addition to the general pain information above, there are several options for the pharmacological treatment of nerve pain. These include:

Treating any underlying source of nerve pain is an effective way of reducing pain. This includes treatment of tone/spasticity which may resolve nerve pain if that is the source.

Antiepileptic oral medication. Used at a low dose (that which will not affect seizures), antiepileptic medication can control nerve pain. These drugs include Tegretol, among others.

Antidepressant oral medication. Also used at a low dose (that which will not affect depression) antidepressants have the ability to assist with neuropathic pain control. Included in this group are Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and amitriptyline (Elavil), among others.

Specifically designed to treat neuropathic pain are the drugs gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica).

All the drugs listed above are started at a low dose. Over time, your body may become tolerant to the drugs so increases in dosage may be needed. However, none of these medications should be stopped without a tapering program. Suddenly stopping these drugs can increase pain and make it more difficult to control neuropathic pain later.

Externally worn nerve stimulators may interfere with the pain signal thereby reducing discomfort.

Nerve blocks, which is medication injected into the body, can anesthetize nerves which leads to less pain.

Surgical treatments of pain include:

Implants of pumps that contain pain medication are available. A pumping device is placed in the abdomen with a tube that is under the skin from the pump to the intrathecal space next to the spinal cord. High doses of medication are delivered to bathe the spinal cord in pain medication. These are often combined with medication for tone/spasticity for a two-part approach to pain control.

Internal implants of spinal cord stimulators can break the pain message from traveling through the spinal cord.

Surgical intervention is reserved for the most intractable pain. This involves severing or destroying nerves or nerve roots therefore making it a least desirable treatment.

For those seeking nonpharmacological neuropathic pain and nocioplastic pain treatment, options are available:

- Distraction, getting involved with other activities has been reported by many individuals as a successful method of treating nerve pain.

- Acupuncture (placement of needle with or without electrical current) and acupressure (pressure over areas of your body) have resulted in the reduction of pain for many individuals.

- Biofeedback is a method of using biological markers such as pulse, respiration, and blood pressure control to reduce nerve pain.

- Exercise and physical and occupational therapy can help provide feedback to your muscles and nerves, providing them with the input they need to help calm them. This can include any type of movement such as yoga or functional electrical stimulation.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a low-level stimulation applied to the skin over the area causing pain. The electrical impulses can ‘block’ the pain signal.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses a large magnet over the skull to align the electrical flow of the brain which may reduce nerve pain in many cases. Studies are ongoing of similar therapy to the spinal cord.

History

Pain has always been an issue with humans. In the 1600s the philosopher, Rene Descartes described pain as a physiological issue. It was not until 1883, that emotional pain was acknowledged by Emil Kräpelin, a German psychiatrist. This started the study of pain as both a physical and mental issue.

In these early years, chloroform was the single drug used. The advent of the use of morphine and heroin was put into use as an alternative. These pain medications were mostly used for surgical interventions and treatment of retractable pain from cancer.

Pain medicine as a specialty in healthcare was developed in the 1960s, again along with rapid developments in cancer treatments. Pain was also starting to be seen even more as a psychological and physiological issue, rather than just a symptom of a disease. Because of this new philosophy, more non-pharmacological treatments started to be explored.

Most of the treatment for pain has focused on pharmacology for treatment. With the advent of cancer treatments to extend people’s lives, pain was felt to be undertreated which led to the increased prescription of pain medications, including opioids. This has led to a rethinking of pain medication with the development of alternatives to prescriptions.

In the 1990s, pain was established as the fifth vital sign. This recognized the importance of pain identification and treatment as a basic part of medical care.

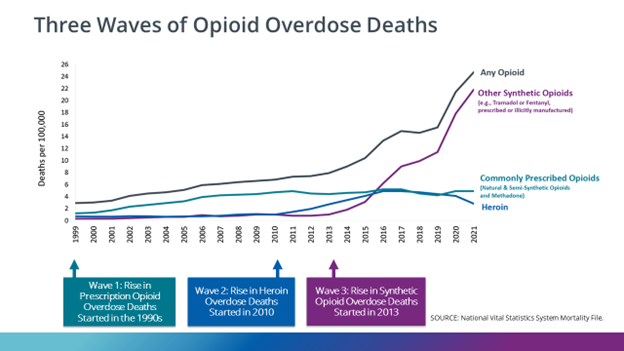

Opioids have become a controversial development for the pharmacological treatment of pain. Originally, the addictive quality of opioid use was not recognized. The opioid epidemic has been documented in three waves. The first wave began in the 1990s with the rise in prescription opioid treatment. In the 2010s, individuals could not get renewed prescriptions of opioids which led to increased use of heroin for pain control. With the development and availability of opioids, particularly fentanyl sold illegally, heroin use dropped, and synthetic opioid deaths are on the rise. Opioids are no longer the preferred treatment for pain due to their addictive properties.

Graphic from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

Click here for a great timeline of the evolution of pain treatment.

Facts and Figures

The CDC reports in 2021 that U.S. adults’ estimations of chronic pain numbered 20.9% (51.6 million) and high-impact chronic pain numbered 6.9% (17.1 million).

Estimates of pain in individuals with spinal cord injury are 60-80%, 1/3 of those individuals report chronic neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain is reported by 10% of people with stroke.

Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis report neuropathic pain at 30%.

Video: Pain Management

Pain Management Education Series Part 1

This webinar focuses on the question: “What is my pain medication?” The topics covered in the session will be an introduction to a fundamental baseline of pain medications, understanding types of pain caused by living with paralysis, and the corresponding medications. There will also be a discussion on potential resources for staying updated about pain medications.

Hosting the session is Jay Gupta, RPh, MSc, MTM Specialist & C-IAYT.

He is the Director of Pharmacy and Integrative Health at Harbor Homes in

Nashua, NH, as well as an MTM consultant and Yoga Therapist. Jay also

is the co-founder of RxRelax, LLC and YogaCaps, Inc.

Recorded January 2019

Pain Management Education Series Part 2

Recorded February 2019

This webinar focuses on understanding opioids and recognizing the signs of addiction. The topics covered in the session include a brief summary of the first webinar, discussing the origin of opioids, how they work, and the causes and treatments of opioid use disorder. There will also be a brief overview of what the final webinar which includes opioid tapering options.

Hosting the session is Jay Gupta, RPh, MSc, MTM Specialist & C-IAYT. He is the Director of Pharmacy and Integrative Health at Harbor Homes in Nashua, NH, as well as an MTM consultant and Yoga Therapist. Jay also is the co-founder of RxRelax, LLC and YogaCaps, Inc.

Pain Management Education Series Part 3

Recorded March 2019

This includes the fundamentals of and factors related to tapering, common questions related to tapering to a non-opioid medication, and different integrative therapy options.

Hosting the session is Jay Gupta, RPh, MSc, MTM Specialist & C-IAYT. He is the Director of Pharmacy and Integrative Health at Harbor Homes in Nashua, NH, as well as an MTM consultant and Yoga Therapist. Jay also is the co-founder of RxRelax, LLC and YogaCaps, Inc.

Resources

If you are looking for more information about pain or have a specific question,

Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis. We encourage you to reach out to support groups and organizations, including:

The Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation Peer Mentor Program

Craig Hospital Exercise and Stretches video

American Heart Association: Pain After Stroke

Stroke Foundation: Pain Management after Stroke

Clinical Guidelines:

CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022

References

Alles SRA, Smith PA. Etiology and Pharmacology of Neuropathic Pain. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Apr;70(2):315-347. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014399. PMID: 29500312.

Bates D, Schultheis BC, Hanes MC, Jolly SM, Chakravarthy KV, Deer TR, Levy RM, Hunter CW. A Comprehensive Algorithm for Management of Neuropathic Pain. Pain Med. 2019 Jun 1;20(Suppl 1):S2-S12. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz075. Erratum in: Pain Med. 2023 Feb 1;24(2):219. PMID: 31152178; PMCID: PMC6544553.

Bernard SA, Chelminski PR, Ives TJ, Ranapurwala SI. Management of Pain in the United States–A Brief History and Implications for the Opioid Epidemic. Health Serv Insights. 2018 Dec 26;11:1178632918819440. doi: 10.1177/1178632918819440. PMID: 30626997; PMCID: PMC6311547.

Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic Pain: An Update on Burden, Best Practices, and New Advances. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2082-2097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7. PMID: 34062143.

Collier R. A Short History of Pain Management. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-E27. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523. PMID: 29311105; PMCID: PMC5760261.

Cruccu G, Truini A. A review of Neuropathic Pain: From Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Pain Ther. 2017 Dec;6(Suppl 1):35-42. doi: 10.1007/s40122-017-0087-0. Epub 2017 Nov 24. PMID: 29178033; PMCID: PMC5701894.

Ferreira ACL, Pereira DS, da Silva SLA, Carvalho GA, Pereira LSM. Validity and Reliability of the Short Form Brief Pain Inventory in Older Adults with Nociceptive, Neuropathic and Nociplastic Pain. Geriatr Nurs. 2023 Jul-Aug;52:16-23. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.04.011. Epub 2023 May 14. PMID: 37192570.

Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W. Nociplastic Pain: Towards an Understanding of Prevalent Pain Conditions. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2098-2110. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5. PMID: 34062144.

Gurba KN, Chaudhry R, Haroutounian S. Central Neuropathic Pain Syndromes: Current and Emerging Pharmacological Strategies. CNS Drugs. 2022 May;36(5):483-516. doi: 10.1007/s40263-022-00914-4. Epub 2022 May 5. PMID: 35513603.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Pain, Disability, and Chronic Illness Behavior; Osterweis M, Kleinman A, Mechanic D, editors. Pain and Disability: Clinical, Behavioral, and Public Policy Perspectives. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1987. 7, The Anatomy and Physiology of Pain. Available here.

Kang J, Cho SS, Kim HY, Lee BH, Cho HJ, Gwak YS. Regional Hyperexcitability and Chronic Neuropathic Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020 Aug;40(6):861-878. doi: 10.1007/s10571-020-00785-7. Epub 2020 Jan 18. PMID: 31955281.

Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Borszcz GS, Cano A, Radcliffe AM, Porter LS, Schubiner H, Keefe FJ. Pain and Emotion: A Biopsychosocial Review of Recent Research. J Clin Psychol. 2011 Sep;67(9):942-68. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20816. Epub 2011 Jun 6. PMID: 21647882; PMCID: PMC3152687.

Masri R, Keller A. Chronic Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;760:74-88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4090-1_5. PMID: 23281514; PMCID: PMC3560294.

Moisset X, Lanteri-Minet M, Fontaine D. Neurostimulation Methods in the Treatment of Chronic Pain. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020 Apr;127(4):673-686. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-02092-y. Epub 2019 Oct 21. PMID: 31637517.

Namkung H, Kim SH, Sawa A. The Insula: An Underestimated Brain Area in Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, and Neurology. Trends Neurosci. 2017 Apr;40(4):200-207. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.02.002. Epub 2017 Mar 15. Erratum in: Trends Neurosci. 2018 Aug;41(8):551-554. PMID: 28314446; PMCID: PMC5538352.

Nijs J, De Baets L, Hodges P. Phenotyping Nociceptive, Neuropathic, and Nociplastic Pain: Who, How, & Why? Braz J Phys Ther. 2023 Jul-Aug;27(4):100537. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2023.100537. Epub 2023 Aug 22. PMID: 37639943; PMCID: PMC10470273.

Nijs J, Lahousse A, Kapreli E, Bilika P, Saraçoğlu İ, Malfliet A, Coppieters I, De Baets L, Leysen L, Roose E, Clark J, Voogt L, Huysmans E. Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future. J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 21;10(15):3203. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153203. PMID: 34361986; PMCID: PMC8347369.

Popkirov S, Enax-Krumova EK, Mainka T, Hoheisel M, Hausteiner-Wiehle C. Functional Pain Disorders – More Than Nociplastic Pain. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;47(3):343-353. doi: 10.3233/NRE-208007. PMID: 32986624.

Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, Guy GP. Chronic Pain Among Adults—United States, 2-19-2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 14, 2023/72(15):379-385.

Scholz J, Finnerup NB, Attal N, Aziz Q, Baron R, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Cruccu G, Davis KD, Evers S, First M, Giamberardino MA, Hansson P, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Nurmikko T, Perrot S, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rowbotham MC, Schug S, Simpson DM, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ, Barke A, Rief W, Treede RD; Classification Committee of the Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group (NeuPSIG). The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):53-59. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001365. PMID: 30586071; PMCID: PMC6310153.

Shala R. Chronic Nociplastic and Neuropathic Pain: How Do They Differentiate? Pain. 2022 Jun 1;163(6):e786. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002576. PMID: 35552318.

Sommer C, Leinders M, Üçeyler N. Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Neuropathic Pain. Pain. 2018 Mar;159(3):595-602. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001122. PMID: 29447138.

Sun L, Peng C, Joosten E, Cheung CW, Tan F, Jiang W, Shen X. Spinal Cord Stimulation and Treatment of Peripheral or Central Neuropathic Pain: Mechanisms and Clinical Application. Neural Plast. 2021 Oct 21;2021:5607898. doi: 10.1155/2021/5607898. PMID: 34721569; PMCID: PMC8553441.

Szok D, Tajti J, Nyári A, Vécsei L. Therapeutic Approaches for Peripheral and Central Neuropathic Pain. Behav Neurol. 2019 Nov 21;2019:8685954. doi: 10.1155/2019/8685954. PMID: 31871494; PMCID: PMC6906810.

Widerström-Noga E. Neuropathic Pain and Spinal Cord Injury: Management, Phenotypes, and Biomarkers. Drugs. 2023 Jul;83(11):1001-1025. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01903-7. Epub 2023 Jun 16. PMID: 37326804.