Bone Health

An essential part of human form and function, bones consist of living cells that are growing and repairing themselves. In the human body, the bones form a skeleton that accounts for approximately 15% of body weight. The skeletal system is one of the body’s major systems. Inside the body, messages are sent to and from bones by the nervous system via nerves to muscles, enabling the bones to work together.

Bone health issues are more common and critical in individuals with paralysis. This includes women, men, and children of all ages. The increased frequency of loss of bone density is due to not bearing weight by standing or walking. A few rare individuals with increased tone (spasticity) in their muscles may have a somewhat lower risk of decreased bone density due to the pulling of the muscles on the bones. However, tone (spasticity) will not prevent or treat bone density loss. The effects of paralysis, including hormonal and cellular changes, affect bone density.

Due to sensation issues, bones can be fractured (broken) without awareness. Issues with bones can lead to pressure injury, difficulty breathing, and chronic pain, which may be presented by referred pain or episodes of autonomic dysreflexia. Life quality can be decreased.

Babies are born with over three hundred bones. This is important to allow body organs to develop without being encased in a rigid bone formation. Many of these bones will merge as a baby grows. Adults have 206 bones. Most bone growth occurs by the age of 13 years for females and 18 years for males. Bone formation is never totally complete, as bones are constantly replacing their cells throughout life. However, full bone development occurs at age 18 years for females and 21 years for males. During our lifetime, bones will continue to replenish themselves.

Bones have four main functions:

1. The primary function of bones is to support the structure and movement of the entire body. Without bones, we would be a mass of tissue. Bones are the basic scaffolding of the body. Bones are what let our bodies move and enable us to perform activities in the environment.

2. Bones protect the internal organs. In the extremities, bones are in the center of the extremities. They are protected by muscles to facilitate movement. In the torso, bones surround the internal organs, allowing the rib cage to protect vital organs. The brain and spinal cord need the most protection. The cranium bones and spinal vertebral bones provide protective encasements for the brain and spinal cord. The brain receives maximum protection from bones as the cranium becomes solid when the growth of the brain slows by adulthood. The bones of the spinal column are small, with discs in between to allow maximum protection of the spinal cord but with flexibility for movement.

3. Minerals are stored in bones, releasing them when the body needs them.

- Calcium provides strength and structural support to the bones. 99% of the body’s calcium is stored in bones.

- Phosphorus works with calcium to form strong bones and teeth. It also helps with energy production and storage. 85% of the body’s phosphorus is stored in the bones.

- Magnesium helps bone structure and calcium absorption.

- Zinc aids bone mineralization.

- Copper assists with the formation of collagen and mineralization of bones.

- Sulfur is in small amounts. It helps with the synthesis of collagen and other proteins.

4. Red bone marrow creates red and white blood cells and platelets. Yellow bone marrow stores fat but can convert to red marrow if needed. The manufacturing of blood cells occurs primarily in the bone marrow (center of bones) of flat and long bones.

Bones that Produce Significant Marrow

| Flat Bones | Long Bones | Vertebrae |

| Pelvis (hip bones) | Femur (thigh bone) | Each of the spine bones |

| Sternum (breastbone) | Humerus (upper arm) | |

| Ribs (surround the chest) | Tibia and Fibula (lower legs) | |

| Skull (head) |

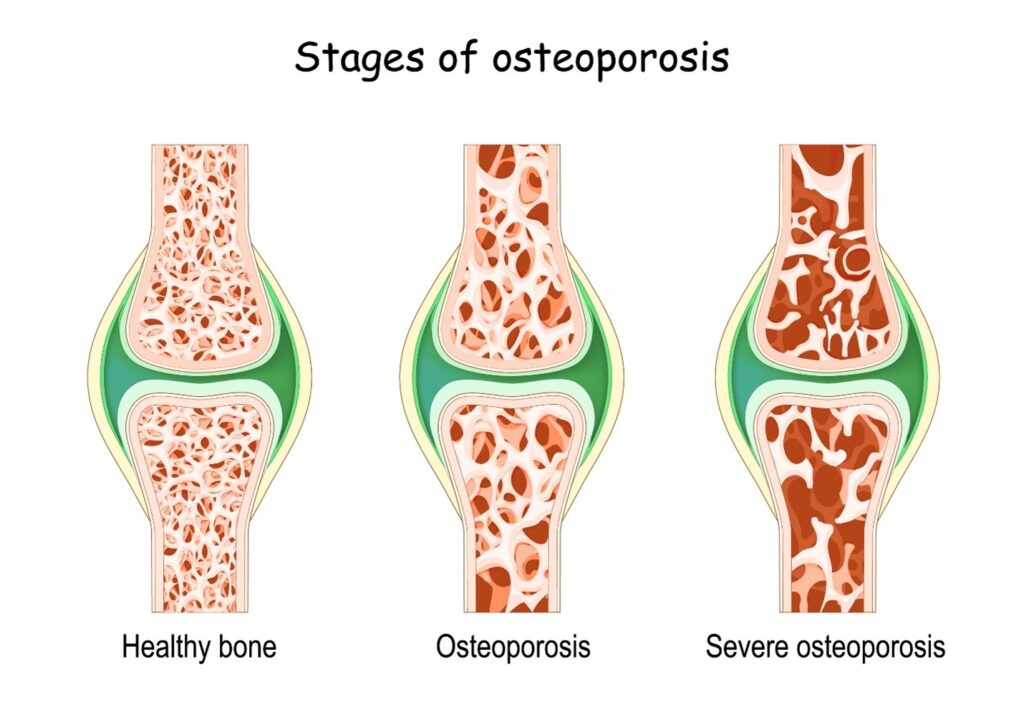

As with all parts of the body, old bone cells are continuously replaced with new bone cells. If the number of new bone cells is not produced to replace the number of destroyed old bone cells, the density of your bones is lessened. This reduces the structure of bones, making them more fragile and easier to break.

Heterotopic Ossification

Occasionally, after paralysis, bone can grow outside of the normal formation. This is called heterotopic ossification (HO). Bone cells can lose their way and grow outside of the bone into the muscle and other tissues.

This may be noted by a joint being stiff, difficult, or unable to be moved; there may be pain or referred pain, episodes of autonomic dysreflexia, swelling, or redness.

- Medications may reduce pain and inflammation.

- Medications to treat HO include etidronate (Didronel) among others.

- Therapy can assist with relaxing the joint and increasing mobility

- Surgery to remove the outgrowth of bone may be needed.

Normal bones have microscopic holes (foramen) throughout. This allows bone blood flow and nerve signal transmission. These tiny holes are functional. They do not interfere with the stability of the bone. Bones have density, which includes these tiny holes.

Bone density, also called bone mass, is the amount of minerals in the bones, most significantly, calcium and other minerals. Fewer minerals in the bones will indicate if a fracture or break in the bone will occur.

If the microscopic holes become larger throughout the bone, with a mild decrease in minerals, osteopenia is diagnosed. This is a mild bone loss or an initial loss in bone density. Osteoporosis is a major loss of bone density or a significant enlargement of the holes in the bones with a large decrease in minerals.

Bone health issues may also develop in addition to paralysis as a risk factor. Other health issues that can affect bones include:

- Osteoarthritis – the deterioration of the cartilage at the ends of your bones in your joints

- Osteogenesis imperfecta – a genetic condition that makes bones brittle

- Paget’s disease – abnormal bone formation

- Osteomyelitis – an infection in bones

- Rickets – softening and lack of bone formation due to lack of vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate

- Fibrous dysplasia – a disease where bone tissue is replaced with weaker fibrous tissue

- Hyperparathyroidism – excessive parathyroid hormone, which can increase bone loss

- Hyperthyroidism – bone loss from the effects of calcium absorption and bone turnover

- Hypogonadism – low levels of sex hormones leading to increased bone reabsorption

- Renal osteodystrophy – chronic kidney disease weakens bones

- Cancer – Ewing sarcoma is a bone cancer, among others

- Rheumatoid arthritis – increases the risk of bone loss and fractures

- Celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease – intolerance to gluten, impairing the absorption of calcium

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) – from smoking, poor nutrition, and medications

- Diabetes – increases the risk of osteoporosis

- Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis – long-term use of steroid hormones

- Paralysis – from a lack of bearing body weight by standing or walking

What are the Symptoms of Bone Health Issues

Symptoms of bone health issues can vary with the diagnosis. Early bone loss may not have any symptoms, but can be diagnosed through testing. Generally, symptoms of a problem in your bones include:

Frequent fractures (broken bones) – are a hallmark indication that the density of your bones is not as it should be.

Bone or joint pain – If you have sensation, you may feel pain at the site of a bone or joint, which indicates something is occurring in that area of your body. If your sensation is challenged, you may have referred pain to your back, shoulder, neck, jaw, or teeth. Typically, but not always, the referred pain is on the same side as the actual pain location. If you have autonomic dysreflexia (AD), the pain could present with an AD episode. Finding the exact location of pain can be a complicated process with sensation issues.

Joint stiffness – degenerative joint diseases may present as stiffness. This could also be due to muscle issues or a lack of movement provided to the joints.

Bone deformities indicate that a bone has been fractured and is now setting itself in an abnormal position. It is also a sign of arthritis. This can later affect functional activities.

Change in posture or height – indicates that there could be an issue, especially in the bones or muscles of the spine (curvature of the spine). This can affect function, especially breathing.

Tingling or weakness – can be indicative of a nerve being pinched by abnormal bone formation, or the nerve can be affecting the bones.

Redness/swelling – may indicate several health issues such as Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) (blood clot), infection, pressure injury, or bone fracture, bone injury, or bone disease.

Hearing loss – the tiniest bones are in the inner ear. Hearing loss, especially on one side, can indicate an issue within the ear bones.

Teeth issues – can be an indication of jawbone or other head bone issues.

Delayed growth in children – can indicate bone issues.

Symptoms of bone density concerns include:

| Common Bone Density Symptoms | Less Common Bone Density Symptoms |

| Frequent fractures (broken bones) | Brittle nails |

| Back pain | Hearing loss |

| Loss of height | Gum disease |

| Stooped posture | Shortness of breath |

It is not unusual for individuals to have no symptoms of decreased bone density until fractures occur. This is especially true for individuals with decreased sensation or those who are not carefully moving their bodies.

How are Bone Health Issues Diagnosed

Bone health issues can be diagnosed by your healthcare professional. There are options for testing that will align with your symptoms.

A physical examination will be completed. You will want to provide a complete understanding of when the issue began, if pain or referred pain is present, how long the problem has existed, if there was an incident that started the issue, and what you have done about your concern. If you have issues with sensation, further testing will be required to assist with the isolation of the area of concern.

Lab testing of blood, urine, or other body fluids may be done to assess your general health and bone health, including bone density. This especially helps if the issue is metabolic. Urine testing can be performed to assess bone turnover markers (how well your bones are replenished). Other lab tests may be performed based on your needs.

Biomarkers New scientific evidence demonstrates that biomarkers (characteristics of internal body functions) may provide information about bone health. Adiponectin (an insulin-sensitivity and inflammation hormone) may be an indicator of bone health.

X-ray can be performed to look for a broken bone (fracture), infection, arthritis, or other bony issues.

Imaging studies, such as a CT scan, can provide more detailed information about bone issues. MRI has more detailed information about soft tissue and bone marrow spaces. PET (positron emission tomography) scan is typically used to locate cancer. Radionuclide bone scan helps locate stress fractures or small breaks in bones.

Bone Density is used to detect osteopenia and osteoporosis, to determine the density of your bones, your risk of breaking a bone, and the effectiveness of treatment for osteoporosis. The test utilizes a Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. This test is an X-ray of specific bones in the body, including the lower spine, hip, and sometimes the forearm. For those with paralysis, the DEXA scan may include the total hip, upper tibia, and lower femur. Individuals with paralysis of the arm or arms often have a bone density test of the forearm due to decreased movement and functional use.

The bone density test indicates the amount of calcium and other bone minerals in a segment of bone. The more minerals in your bones (the density of minerals), the less likely they are to break. An assessment of the percentage of body fat and muscle mass is also done. The typical DEXA scan does not detect bone fractures or scan the entire body.

Decreases in bone density are often thought of in older women. However, men, women, and children with paralysis are more susceptible to low bone density and frequent bone fractures (breaks) due to a lack of movement and weight being put through the bones. Changes in hormone levels, due to menopause or low testosterone, and testosterone replacement therapy can lead to lower bone strength.

The DEXA scan is painless. You will need to lie on the scanning table, which can often be lowered for transfers. If the table at your facility does not lower, you will need to ask for assistance. The technician will place your body into position so the scan can be performed. Usually, you can stay seated if only the forearm is being scanned. The scanner device moves over your body but does not touch you.

Bone density testing is measured in T scores.

Osteopenia is indicated with a T-score of -1.0 and -2.4 compared to a standardized healthy young adult score. This is early bone loss. A Z-score compares your results to individuals your age and gender. There may not be any symptoms with osteopenia. Intervention treatment is needed. Not treating osteopenia leads to osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is indicated with a T-score of -2.5 or lower compared to a standardized healthy young adult score. This indicates severe bone loss. A Z-score compares your results to individuals your age and gender. With osteoporosis, you may have no symptoms. If you have sensation, there may be pain, tenderness, or bone fractures (breaks). If sensation is decreased, you may have referred pain, or you may assume there is a bone fracture (break) due to misalignment of a body part. Treatment is needed. Osteoporosis is more challenging to correct.

What are the Treatments For Healthy Bones

The best treatment for healthy bones is to prevent bone density loss. To ensure your bones are healthy or that early attention is needed, routine DEXA scans and/or urine testing are critical. Individuals who are preventing or treating bone loss will require a combination of treatments and therapies.

Prevention of bone loss treatment

- Move your body carefully. Throwing your arms or legs can injure them.

- Check to ensure your arms and legs are properly placed before moving your chair or transferring.

- Review your medications with your healthcare professional. Steroids, blood thinners, opioids, benzodiazepines, proton-pump inhibitors, and anti-seizure medications can increase bone loss. These are all necessary medications prescribed for serious medical conditions. However, a different form of the medication may be better for your condition.

- Diet can add calcium and vitamin D. Good examples are leafy greens, fatty fish, egg yolks, and fortified foods. Vitamin K2, which is found in grass-fed animals, helps direct calcium to the bones. Protein builds muscles, magnesium, zinc, and vitamin C contribute to bone health. Check with your healthcare professional or dietician to ensure you need these supplements, that they will not interact with other medications, and that you take the correct amount for your body.

- Smoking and alcohol can interfere with body processes such as bone mineralization.

- Maintain a healthy weight; being under- or overweight can interfere with bone health.

- Your healthcare professional may recommend supplements such as calcium and vitamin D to prevent bone loss.

- Prevent falls by checking to ensure wheelchair brakes are secure, that you are transferring safely, removing tripping hazards, adding grab bars, and removing clutter. Ensure your routes outside of the home are safe for wheels. Notify your city if the sidewalks are bumpy or if a wheelchair curb cut is needed.

- Aquatic therapy utilizes the buoyancy of the water, which can assist with ease of movement. This can reduce stress on joints while strengthening muscles.

- Gait training using braces, exoskeletons, or weight-supported walking can improve bone density if you qualify for these therapies.

- Provide movement to your body to stretch muscles, which cause the tendons to pull on bones. This assists with bearing weight through your bones.

- Resistance training using your body or extremity weight, resistance bands, or weights helps provide movement. Either by doing the exercise yourself or having someone do it to your body. Extremity ‘loops’ can be created to Velcro around a leg, with a loop attached to use your arms to move your legs.

Treatment for bone density issues depends on the individual. Preventative actions should continue to be taken if allowed, in addition to treatment for bone density issues.

Treatment for bone fractures (breaks) must occur immediately, even if you are not having pain. Getting the bone back into alignment is critical for movement (now and in the future). Correct positioning of bones helps prevent an increase in tone (spasticity), reduces the risk of pressure injury, may decrease episodes of autonomic dysreflexia (AD), and further injury to the bones, muscles, and tendons.

- Supplements of calcium and vitamin D are typically a part of the treatment plan for individuals with paralysis.

- Anti-osteoporosis medication has mixed results with individuals with paralysis. Check with your healthcare professional before taking this medication.

- Surgery When a bone breaks, surgery using small metal plates is performed to attach to healthy bone above and below the fracture.

- Casting If osteopenia or osteoporosis is present when the fracture occurs, there may not be healthy bone to attach the plate. Casting is then done to stabilize the limb. This can greatly extend recovery time.

- Therapy will be needed when you can move or have your bone moved to reinvigorate the muscles.

Rehabilitation and Therapies

Prevention is the key to avoiding bone health issues. These therapies may be used to prevent bone density issues or to aid in recovery from osteopenia or osteoporosis.

- Movement is absolutely necessary for bone health. Range of motion or stretching exercises should be done to all of the joints in the body to provide tendon stretching on the bones. Because you cannot see this working inside your body, people often give up this twice-daily activity. It is critical to your bone health. Many individuals find movement to have a positive mental wellness effect.

- Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) uses electrical impulses from outside of the body which helps stimulate muscles and encourages bone growth. In some cases, this treatment may help reverse bone density loss. FES biking is an excellent option; however, local units may also help.

- A Standing Frame is a device that you transfer to, use soft straps to block your joints, and then use a pump to put your body in a standing position. This puts your body weight through the lower bones for strengthening. Typically, individuals use this device for one hour a day.

- Before using a standing frame, you need to check with your healthcare professional to ensure your bones are strong enough for this activity and that you do not have any hidden blood clots. You may not be able to stand on the first attempt due to orthostatic hypotension (OH) (blood pressure drop on standing). But you can slowly build up tolerance to a full stand over time.

- Many individuals and family members have an overwhelming reaction to standing when it has not been done for quite a while. As it should be, individuals are thinking about standing, but be prepared that seeing yourself stand makes a difference in your body image and mind.

- Many payors are now covering standing frames for individuals with paralysis. A prescription is required. Some options can be added to enhance standing, such as a tray attachment. Others have a reciprocal arm and leg sliders for additional exercise. Others have wheels to move about. Options are often not covered.

- Vibration plates are sometimes used to stimulate movement in the legs. Your feet can be placed on the vibration plate. They are more helpful when used with a standing frame. This is typically more of a preventive treatment.

History

Bones have been the subject of mankind for centuries. In the Renaissance, anatomical studies were about structure and function.

There have been advances through the years, but advancements in bone health research blossomed in the 1970s with the coordination of research through the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. This group focuses on bone biology, osteoporosis, and bone diseases.

New ideas about bone density and paralysis have evolved in recent years. In the late 1990s, the Christopher Reeve recovery project catapulted bone health in individuals with paralysis. The need for physical movement is essential. Bone density issues are often a study performed in space due to weightlessness and rebuilding bone after astronauts return to earth.

Today, bone health involves genetics, nutrition, physical activity, and the reduction of smoking and alcohol. Newer research surrounds the gut microbiome in maintaining bone health.

Facts and Figures

With neurological injury from trauma, 20 to 40% of bone density can be lost in the first year. Neurological injury from disease has more variability in affecting bone density depending on movement ability and progression of the disease.

Of the individuals with complete spinal cord injury, 50% will develop osteoporosis within one year. Long-term follow-up indicates 80% of individuals with complete SCI will have osteoporosis.

Fragility fracture (due to low bone density) is the most common type of fracture with paralysis.

Resources

If you are looking for more information on bone health or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available business weekdays, Monday through Friday, toll-free at 800-539-7309 or online at ChristopherReeve.org/Ask.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains fact sheets on osteoporosis and osteomyelitis. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to also reach out to bone health support groups and organizations, including:

American Academy of Family Physicians. NIH Releases Statement on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(1):161-162.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004.

Clinical Guideline:

Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA). Bone Health and Osteoporosis Management in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Providers, 2022.

References

Agrawal A, Ellegaard M, Haanes KA, Wang N, Gartland A, Ding M, Praetorius H, Jørgensen NR. Absence of P2Y2 Receptor Does Not Prevent Bone Destruction in a Murine Model of Muscle Paralysis-Induced Bone Loss. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 May 26;13:850525. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.850525. PMID: 35721713; PMCID: PMC9204296.

Atan T, Ekinci U, Uran San A, Demir Y, Guzelkucuk U, Kesikburun S, Uyar Koylu S, Tan AK. The Relationship Between Falls and Hip Bone Mineral Density of Paretic and Nonparetic Limbs After Stroke. PM R. 2025 May;17(5):529-538. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.13290. Epub 2024 Nov 27. PMID: 39604710.

Bauman WA. Pharmacological Approaches for Bone Health in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2021 Oct;60:346-359. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2021.07.024. Epub 2021 Sep 14. PMID: 34534754.

Bauman WA, Cardozo CP. Osteoporosis in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury. PM R. 2015 Feb;7(2):188-201; quiz 201. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.08.948. Epub 2014 Aug 27. PMID: 25171878.

Bosques G, Martin R, McGee L, Sadowsky C. Does Therapeutic Electrical Stimulation Improve Function in Children with Disabilities? A Comprehensive Literature Review. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2016 May 31;9(2):83-99. doi: 10.3233/PRM-160375. PMID: 27285801.

Bullock WA, Hoggatt AM, Horan DJ, Lewis KJ, Yokota H, Hann S, Warman ML, Sebastian A, Loots GG, Pavalko FM, Robling AG. Expression of a Degradation-Resistant β-Catenin Mutant in Osteocytes Protects the Skeleton From Mechanodeprivation-Induced Bone Wasting. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Oct;34(10):1964-1975. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3812. Epub 2019 Aug 5. PMID: 31173667; PMCID: PMC6813861.

Cirnigliaro CM, Myslinski MJ, Asselin P, Hobson JC, Specht A, La Fountaine MF, Kirshblum SC, Forrest GF, Dyson-Hudson T, Spungen AM, Bauman WA. Progressive Sublesional Bone Loss Extends into the Second Decade After Spinal Cord Injury. J Clin Densitom. 2019 Apr-Jun;22(2):185-194. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2018.10.006. Epub 2018 Oct 31. PMID: 30503961.

Curley N, Yang Y, Dean J, Salorio C, Sadowsky C. Description of Bone Health Changes in a Cohort of Children With Acute Flaccid Myelitis (AFM). Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2022 Winter;28(1):42-52. doi: 10.46292/sci21-00035. Epub 2022 Jan 19. PMID: 35145334; PMCID: PMC8791422.

Davis GM, Hamzaid NA, Fornusek C. Cardiorespiratory, Metabolic, and Biomechanical Responses During Functional Electrical Stimulation Leg Exercise: Health and Fitness Benefits. Artif Organs. 2008 Aug;32(8):625-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2008.00622.x. PMID: 18782133.

Deley G, Denuziller J, Babault N. Functional Electrical Stimulation: Cardiorespiratory Adaptations and Applications for Training in Paraplegia. Sports Med. 2015 Jan;45(1):71-82. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0250-2. PMID: 25205000.

Ding Y, Cui Y, Yang X, Wang X, Tian G, Peng J, Wu B, Tang L, Cui CP, Zhang L. Anti-RANKL monoclonal antibody and bortezomib prevent mechanical unloading-induced bone loss. J Bone Miner Metab. 2021 Nov;39(6):974-983. doi: 10.1007/s00774-021-01246-x. Epub 2021 Jul 1. PMID: 34212247.

Echevarria-Cruz E, McMillan DW, Reid KF, Valderrábano RJ. Spinal Cord Injury Associated Disease of the Skeleton, an Unresolved Problem with Need for Multimodal Interventions. Adv Biol (Weinh). 2025 Jun;9(6):e2400213. doi: 10.1002/adbi.202400213. Epub 2024 Jul 29. PMID: 39074256.

Edmiston T, Cabahug P, Recio A, Sadowsky CL. Bone Health following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Guide to Assessment and Management. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2025 Feb;36(1):99-110. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2024.07.007. Epub 2024 Sep 7. PMID: 39567041.

Ellman R, Grasso DJ, van Vliet M, Brooks DJ, Spatz JM, Conlon C, Bouxsein ML. Combined Effects of Botulinum Toxin Injection and Hind Limb Unloading on Bone and Muscle. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014 Mar;94(3):327-37. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9814-7. Epub 2013 Nov 17. PMID: 24240478; PMCID: PMC3921683.

Giangregorio LM, Gibbs JC, Craven BC. Measuring Muscle and Bone in Individuals with Neurologic Impairment; Lessons Learned About Participant Selection and pQCT Scan Acquisition and Analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Aug;27(8):2433-46. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3572-0. Epub 2016 Mar 30. PMID: 27026329.

Ghasem-Zadeh A, Galea MP, Nunn A, Panisset M, Wang XF, Iuliano S, Boyd SK, Forwood MR, Seeman E. Heterogeneity in Microstructural Deterioration Following Spinal Cord Injury. Bone. 2021 Jan;142:115778. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115778. Epub 2020 Nov 28. PMID: 33253932.

Gorgey AS, Witt O, O’Brien L, Cardozo C, Chen Q, Lesnefsky EJ, Graham ZA. Mitochondrial Health and Muscle Plasticity After Spinal Cord Injury. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019 Feb;119(2):315-331. doi: 10.1007/s00421-018-4039-0. Epub 2018 Dec 11. PMID: 30539302.

Han S, Shin S, Kim O, Hong N. Characteristics Associated with Bone Loss after Spinal Cord Injury: Implications for Hip Region Vulnerability. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2023 Oct;38(5):578-587. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2023.1795. Epub 2023 Oct 10. PMID: 37816499; PMCID: PMC10613772.

Hoover C, Schuerger W, Balser D, McCracken P, Murray TA, Morse L, Parr A, Samadani U, Netoff TI, Darrow DP. Neuromodulation Through Spinal Cord Stimulation Restores Ability to Voluntarily Cycle After Motor Complete Paraplegia. J Neurotrauma. 2024 May;41(9-10):1163-1171. doi: 10.1089/neu.2022.0322. Epub 2023 Mar 22. PMID: 36719784.

Ibitoye MO, Hamzaid NA, Ahmed YK. Effectiveness of FES-Supported Leg Exercise for Promotion of Paralysed Lower Limb Muscle and Bone Health-A Systematic Review. Biomed Tech (Berl). 2023 Mar 1;68(4):329-350. doi: 10.1515/bmt-2021-0195. PMID: 36852605.

Jones LM, Goulding A, Gerrard DF. DEXA: A Practical and Accurate Tool to Demonstrate Total and Regional Bone Loss, Lean Tissue Loss and Fat Mass Gain in Paraplegia. Spinal Cord. 1998 Sep;36(9):637-40. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100664. PMID: 9773449.

Kim JH, Park YS, Oh KJ, Choi HS. Surgical Treatment of Severe Osteoporosis Including New Concept of Advanced Severe Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2017 Dec;3(4):164-169. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2017.11.006. Epub 2017 Dec 18. PMID: 30775525; PMCID: PMC6372822.

Fattal C, Schmoll M, Le Guillou R, Raoult B, Frey A, Carlier R, Azevedo-Coste C. Benefits of 1-Yr Home Training With Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling in Paraplegia During COVID-19 Crisis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021 Dec 1;100(12):1148-1151. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001898. PMID: 34596097; PMCID: PMC8594387.

Lee HK, Notario GR, Won SY, Kim JH, Lee SM, Kim HS, Cho SR. Elevated Sclerostin Levels Contribute to Reduced Bone Mineral Density in Non-Ambulatory Stroke Patients. Bone Rep. 2025 Feb 11;25:101829. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2025.101829. PMID: 40225703; PMCID: PMC11986488.

Maïmoun L, Fattal C, Sultan C. Bone Remodeling and Calcium Homeostasis in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Review. Metabolism. 2011 Dec;60(12):1655-63. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.04.005. Epub 2011 May 31. PMID: 21632079.

Matthys T, Ho Dang HA, Rafferty KL, Herring SW. Bone and Cartilage Changes in Rabbit Mandibular Condyles After 1 Injection of Botulinum Toxin. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015 Dec;148(6):999-1009. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.05.034. PMID: 26672706; PMCID: PMC4683608.

McMillan DW, Nash MS, Gater DR Jr, Valderrábano RJ. Neurogenic Obesity and Skeletal Pathology in Spinal Cord Injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2021;27(1):57-67. doi: 10.46292/sci20-00035. PMID: 33814883; PMCID: PMC7983641.

Modlesky CM, Majumdar S, Narasimhan A, Dudley GA. Trabecular Bone Microarchitecture is Deteriorated in Men with Spinal Cord Injury. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Jan;19(1):48-55. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301208. PMID: 14753736.

Morse LR, Biering-Soerensen F, Carbone LD, Cervinka T, Cirnigliaro CM, Johnston TE, Liu N, Troy KL, Weaver FM, Shuhart C, Craven BC. Bone Mineral Density Testing in Spinal Cord Injury: 2019 ISCD Official Position. J Clin Densitom. 2019 Oct-Dec;22(4):554-566. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2019.07.012. Epub 2019 Aug 3. PMID: 31501005.

Nistor-Cseppento CD, Gherle A, Negrut N, Bungau SG, Sabau AM, Radu AF, Bungau AF, Tit DM, Uivaraseanu B, Ghitea TC, Uivarosan D. The Outcomes of Robotic Rehabilitation Assisted Devices Following Spinal Cord Injury and the Prevention of Secondary Associated Complications. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Oct 13;58(10):1447. doi: 10.3390/medicina58101447. PMID: 36295607; PMCID: PMC9611825.

Otzel DM, Conover CF, Ye F, Phillips EG, Bassett T, Wnek RD, Flores M, Catter A, Ghosh P, Balaez A, Petusevsky J, Chen C, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Jiron JM, Bose PK, Borst SE, Wronski TJ, Aguirre JI, Yarrow JF. Longitudinal Examination of Bone Loss in Male Rats After Moderate-Severe Contusion Spinal Cord Injury. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019 Jan;104(1):79-91. doi: 10.1007/s00223-018-0471-8. Epub 2018 Sep 14. PMID: 30218117; PMCID: PMC8349506.

Pietraszkiewicz F, Pluskiewicz W, Drozdzowska B. Skeletal and Functional Status in Patients with Long-Standing Stroke. Endokrynol Pol. 2011 Jan-Feb;62(1):2-7. PMID: 21365571.

Runciman P, Tucker R, Ferreira S, Albertus-Kajee Y, Micklesfield L, Derman W. Site-Specific Bone Mineral Density Is Unaltered Despite Differences in Fat-Free Soft Tissue Mass Between Affected and Nonaffected Sides in Hemiplegic Paralympic Athletes with Cerebral Palsy: Preliminary Findings. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016 Oct;95(10):771-8. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000532. PMID: 27149600.

Sadowsky CL, Mingioni N, Zinski J. A Primary Care Provider’s Guide to Bone Health in Spinal Cord-Related Paralysis. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2020 Spring;26(2):128-133. doi: 10.46292/sci2602-128. PMID: 32760192; PMCID: PMC7384544.

Sadowsky CL, McDonald JW. Activity-Based Restorative Therapies: Concepts and Applications in Spinal Cord Injury-Related Neurorehabilitation. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(2):112-6. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.61. PMID: 19489091.

Sutor TW, Kura J, Mattingly AJ, Otzel DM, Yarrow JF. The Effects of Exercise and Activity-Based Physical Therapy on Bone after Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 6;23(2):608. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020608. PMID: 35054791; PMCID: PMC8775843.

Tan CO, Battaglino RA, Doherty AL, Gupta R, Lazzari AA, Garshick E, Zafonte R, Morse LR. Adiponectin is Associated with Bone Strength and Fracture History in Paralyzed Men with Spinal Cord Injury. Osteoporos Int. 2014 Nov;25(11):2599-607. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2786-2. Epub 2014 Jul 1. PMID: 24980185; PMCID: PMC4861654.

Teguh DA, Nustad JL, Craven AE, Brooks DJ, Arlt H, Hu D, Baron R, Lanske B, Bouxsein ML. Abaloparatide Treatment Increases Bone Formation, Bone Density and Bone Strength without Increasing Bone Resorption in a Rat Model of Hindlimb Unloading. Bone. 2021 Mar;144:115801. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115801. Epub 2020 Dec 16. PMID: 33338664.

Tretter BL, Dolbow DR, Ooi V, Farkas GJ, Miller JM, Deitrich JN, Gorgey AS. Neurogenic Aging After Spinal Cord Injury: Highlighting the Unique Characteristics of Aging After Spinal Cord Injury. J Clin Med. 2024 Nov 27;13(23):7197. doi: 10.3390/jcm13237197. PMID: 39685657; PMCID: PMC11642369.Tsukamoto M, Sakai A. [Immobilization and bone remodeling disorder.]. Clin Calcium. 2017;27(12):1723-1730. Japanese. PMID: 29179166.

Tsuzuku S, Ikegami Y, Yabe K. Bone Mineral Density Differences Between Paraplegic and Quadriplegic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Spinal Cord. 1999 May;37(5):358-61. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100835. PMID: 10369173.

Ung RV, Rouleau P, Guertin PA. Functional and Physiological Effects of Treadmill Training Induced by Buspirone, carbidopa, and L-DOPA in Clenbuterol-Treated Paraplegic Mice. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012 May;26(4):385-94. doi: 10.1177/1545968311427042. Epub 2011 Dec 9. PMID: 22157146.

Zhao D, Sun L, Zheng W, Hu J, Zhou B, Wang O, Jiang Y, Xia W, Xing X, Li M. Novel Mutation in LRP5 Gene Cause Rare Osteosclerosis: Cases Studies and Literature Review. Mol Genet Genomics. 2023 May;298(3):683-692. doi: 10.1007/s00438-023-02008-2. Epub 2023 Mar 27. PMID: 36971833; PMCID: PMC10133070.