Muscular Dystrophy

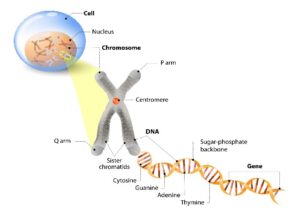

Dystrophy is a weakening, degenerative condition that occurs due to genetic alterations. It can occur anywhere in the body, including internal organs or body tissue. Most often, it is due to inherited or spontaneous genetic mutations. When the muscles are specifically affected, Muscular Dystrophy (MD) is diagnosed. It is a rare neurological disease.

Muscular Dystrophies (MD) are diagnosed when genes in the body stop producing, change, or affect the body’s internal protein production. This can occur due to genetically inherited traits or spontaneously. MD mostly affects skeletal muscle groups (muscles that attach to bones). However, the heart muscle and muscles used for breathing can also be affected. The genetic type of MD determines body effects.

Muscular Dystrophies (MD) are diagnosed when genes in the body stop producing, change, or affect the body’s internal protein production. This can occur due to genetically inherited traits or spontaneously. MD mostly affects skeletal muscle groups (muscles that attach to bones). However, the heart muscle and muscles used for breathing can also be affected. The genetic type of MD determines body effects.

Genetic occurrences of muscular dystrophy can occur in three ways:

- A combination of a non-affected gene from one parent and an affected gene from the other.

- Both parents contribute an affected gene.

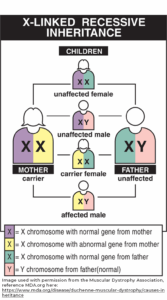

- An affected X gene is passed from the mother to a boy child.

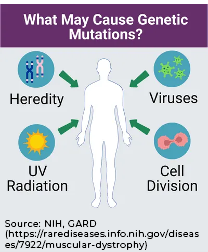

Spontaneous development of MD occurs when a genetic mutation leads to an inability for the gene protein to function as needed. The reason for this change may be unknown, resulting from a virus, radiation, or an environmental factor.

Both those with genetically inherited MD and spontaneous MD can pass the affected gene to their children.

With MD, the body cannot function as needed to maintain muscle health and function. The specific type of MD is determined by the affected gene or gene sequence. Different parts of the body can be affected by MD depending on the type of genetic issue. Body functions that involve muscles are affected, such as stiffening of the joints and muscles, trouble walking, challenges in swallowing and choking, breathing, and heart issues (the heart is a muscle).

MD most commonly affects young boys, as with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). However, depending on the genes affected, girls and adults can also have MD. The general effects of MD include muscle wasting and a reduction in muscle mass. Muscular Dystrophy diseases are progressive, meaning they continue to advance over time.

Muscular Dystrophy is being researched to understand genetic factors. Treatments can and are being developed to treat the genetic source. Each type of MD is related to a specific genetic cause and affects different muscle groups.

Types of Muscular Dystrophy

Overall, more than 30 forms of Muscular Dystrophy have been identified. These types of MD have differing effects, groups of muscle weaknesses, age of onset, progression rates, symptom severity, and family history. The following are more common overall MD types. Several of these common types include a number of subtypes.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is the most common form of MD. It mostly appears in boys between the ages of 2 and 6 years, but symptoms can develop earlier or later in life. It has been diagnosed in some girls, depending on the genetic mutation.

DMD affects the production and management of dystrophin protein, which is responsible for maintaining muscle fiber integrity. Dystrophin maintains and strengthens muscle fibers, which keeps the muscles safe from injury, especially the heart muscle. As a part of the body’s dystrophin-associated protein complex (DAPC), dystrophin protects the structure of muscles throughout the body and protects them from injury.

The first symptoms of DMD usually appear as weakness in the upper legs and pelvis. It then affects the upper arms. This progression may or may not be noticeable. Some common symptoms include loss of leg and arm reflexes, waddling gait, falls, clumsiness, difficulty changing positions from sitting to standing, getting out of bed, going up stairs, challenges with running and jumping, changes in posture, difficulty breathing and coughing, and heart problems. The outer body may not show decreases in muscle mass in affected areas, as internal connective tissue can increase. Infections in the respiratory system, osteoporosis, osteopenia (weak bones), and scoliosis (curved spine) can develop as muscles weaken. Mental sharpness can also be affected, especially in the later stages.

In DMD, progression is often rapid. Severe muscle weakness is a hallmark of the disease. In addition to muscle weakness in the extremities, other affected body parts include the heart, lungs, throat, stomach, intestines, and spine. The use of assistive mobility devices, including wheelchairs, often becomes necessary by the age of 12 or in early teenage years. In some cases, mechanical ventilation will be required to support breathing.

The symptoms can vary in speed of onset, rate, and specific locations. This results in differing abilities among individuals. Life expectancy was in the 20s and 30s. With the advent of the use of glucocorticoids, nutritional support, and respiratory and cardiac care, life expectancy for DMD has increased into the late 50s.

Becker Muscular Dystrophy (BMD) symptoms are similar to DMD, but often with milder effects, particularly in the muscle weakness of the upper legs and upper arms. Onset typically occurs later in life, either in childhood or adulthood, between the ages of 11 through 25. Due to the less severe symptoms, assisted mobility devices are not typically used until the mid-30s. As with DMD, genetic mutation is the production and management of dystrophin protein, which controls muscle fiber integrity. Affected body parts are the same as in DMD; however, the severity is less.

Congenital Muscular Dystrophy (CMD) appears at birth or in early childhood. This dystrophy is rare. Both males and females can be affected. CMD affects the web of extracellular matrix of muscle cells, which consists of proteins that cause muscles to contract, connects muscle cells, transmit signals among cells, and repair and promote muscle development. Motor function and muscle control are involved.

Distal Dystrophy(DD) is a rare type of dystrophy that can affect both males and females. Symptoms begin in adults. Muscles of the feet, hands, lower legs, lower arms, and heart are affected.

Emery-Dreifuss Type (EDMD) is a rare type of dystrophy that affects both males and females. Genetically, emerin, a small protein found on the X chromosome, is not created for the cell membrane. Involved are skeletal (bones) and heart muscles. Affected are the joints, which can lead to deformities and contractures, especially in the elbows, ankles, and neck. The understanding of how this leads to EDMD is not yet understood.

Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD) is the third most common dystrophy. Affected are the muscles in the face, shoulders, and upper arms. As with all dystrophies, weakness and muscle wasting are the symptoms. FSHD is caused by a unit of DNA named D4Z4. This unit contracts, thereby restricting the needed protein.

Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy (LGMD) affects the hips and shoulders. Muscles can become weak, wasted, or atrophy, which can affect functions of surrounding muscles. There are over 30 types of gene mutations that lead to LGMD. These genetic alterations affect the development of proteins for muscle function. Some, but not all, are the same genetic issues as with DMD and Becker’s. Others have common genetic mutations with Emery-Dreifuss. Some genetic alterations are unique to LGMD.

Myotonic Dystrophy (DM) appears mostly between the ages of 10 and 30 years, with some cases diagnosed between birth and 70 years. First signs are weakness in the face, neck, arms, hands, hips, and lower legs. Prolonged muscle contractions and weakness are symptoms. Other systems may be affected, including the heart, lungs, intestines, brain, eyes, and endocrine systems. Two types of DM occur, DM1 and DM2. Both are due to the expanded stretches of DNA from different genes, with effects on both voluntary and involuntary muscles.

Myotonic dystrophy is a rare, multi-systemic, progressive, inherited disease that is estimated to affect as many as 1 in 2,100 people. Myotonic dystrophy is the most common form of adult muscular dystrophy and considered the most variable of all known conditions. The symptoms become more severe with each generation – known as genetic anticipation – yet there is currently no cure and there are no FDA approved treatments.

The disease is caused by a mutation in the DMPK gene, resulting in myotonic dystrophy type one, and in the CNBP gene, resulting in myotonic dystrophy type two. These mutations prevent the genes from carrying out their functions properly, impacting multiple body systems.

The genetic mutation is an autosomal dominant mutation, where one copy of the altered gene is sufficient to cause the disorder. As a result, affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing on the mutated gene to their children. A child is equally likely to have inherited the mutated gene from either parent. If both parents do not have the disease, their children cannot inherit it.

Through this inherited genetic anomaly, individuals with myotonic dystrophy experience varied and complex symptoms, from skeletal muscle problems, to heart, breathing, digestive, hormonal, speech and swallowing, diabetic, immune, excessive daytime sleepiness, early cataracts and vision, and cognitive difficulties.

Myotonic dystrophy is a highly variable and complicated disorder. The systems affected, the severity of symptoms, and the age of onset of those symptoms vary greatly between individuals, even in the same family. In general, the younger an individual is when symptoms first appear, the more severe symptoms are likely to be.

A complete diagnostic evaluation, which includes family history, physical examination, and medical tests, is typically required for a presumptive diagnosis of myotonic dystrophy. The presence of the disorder can then be confirmed by genetic testing. Prenatal testing, where the DNA of the fetus is checked for the presence of the myotonic dystrophy mutation, is also available. Despite the availability of simple genetic tests, misdiagnoses persist for decades.

Delays in diagnosing myotonic dystrophy are common, sometimes over a decade long. This is usually because of the lack of familiarity with the disease on the part of clinicians and that more common diseases with symptoms that mimic myotonic dystrophy must typically first be ruled out before this disorder is considered.

Oculopharyngeal Type (OPMD) develops in middle age. Symptoms include drooping eyelids, eye muscle weakness, and swallowing challenges, most notably with food. The genetic link to OPMD is overproduction of amino acids due to the gene PABPN1, which causes proteins to clump together, affecting cell function.

Dystroglycanopathy is a phenomenon in MD that was discovered in 2010. Individuals across various types and with serious cases of MD are affected. Initial symptoms are similar to DMD. Sugar chain structures of dystroglycan protein in the DAG1 genes are disrupted. Eighteen genes have been identified as causative agents. Research about early diagnosis, understanding genetic issues, and treatments is underway.

Symptoms

Muscular dystrophy is a collective name for a variety of types of the disease. In different forms of MD, different symptoms appear that affect various parts of the body. Overall, the symptoms that are first noted in general are:

- Muscle weakness in groups of muscles of the body

- Muscle wasting and atrophy (muscles become smaller)

- Muscle spasms (tone), contractures (stiffening or shortening of tendons)

- Muscle aches and pains

Because muscles may not function appropriately with age or developmental level, some of the symptoms that develop are:

- Tripping

- Falling

- Difficulty in running and jumping

- Late walking development, waddle style walking, toe stepping

- Foot Drop

- Activities of daily living decreased, such as dressing, feeding, or, in some cases, swallowing

- Challenges in changing position from lying to sitting

- Skin and nail problems from altered walking

- Developmental milestones delay

Other complications of MD may include the following issues, depending on the specific MD diagnosis. It is important to highlight that individuals with MD will have some or all of these concerns:

- Learning and cognitive abilities

- Decreased heart function

- High blood pressure

- Cardiomyopathy

- Heart problems and heart failure

- Coughing difficulty

- Diaphragm weakness

- Difficulty breathing requiring mechanical ventilation

- Recurring pneumonia

- Difficulty eating and swallowing

- Malnutrition

- Loss of muscle mass

- Muscle contractures

- Weaknesses

- Walking challenges

- Difficulty using arms

- Inflammation in the body

- Fibrosis

- Brittle and weak bones, including low bone density

- Scoliosis

- Seizures

Diagnosing

There are several opportunities to diagnose muscular dystrophy. These can occur before pregnancy, during pregnancy, after birth, or due to symptoms later in life.

Diagnostic Tests Before and During Pregnancy: A genetic counselor is usually seen if there is a concern about inherited diseases. These healthcare professionals will create a genetic history of both parents and families and provide information about the risks of your child inheriting a genetic condition. They may recommend further testing.

Diagnostic Tests Before and During Pregnancy: A genetic counselor is usually seen if there is a concern about inherited diseases. These healthcare professionals will create a genetic history of both parents and families and provide information about the risks of your child inheriting a genetic condition. They may recommend further testing.

When pregnancy has occurred, elective testing can help parents with future planning. Amniocentesis (performed at 15-18 weeks of pregnancy) and/or Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) (performed at 10-13 weeks of pregnancy) are tests for genetic conditions. In amniocentesis, a small amount of fluid is removed from the uterus. CVS samples tissue of the placenta. Both test specimens are collected with a needle to withdraw the sample. An ultrasound is used to ensure the protection of the fetus. The tissue is then tested for genetic issues. The genetic counselor will develop a family tree and provide percentages of risk.

Diagnostic Tests for Children and Adults. Most testing for MD is performed after birth, in childhood, or in adulthood when symptoms appear. You or your child’s healthcare professional will perform a comprehensive medical examination. They will ask questions about the exact symptoms, when symptoms first appeared, specifically at what age, and the muscle groups that are affected.

Testing will be performed to verify the diagnosis. Testing for MD may include some of the following procedures. At times, if a genetic link is known and symptoms match those of MD, the tests may not be necessary or may be used for confirmation.

Blood Tests

- Creatine Kinase (CK) can assess if too much of the CK enzyme is in the blood. It may indicate neuromuscular conditions such as MD.

- Aldolase is another blood test that measures enzymes that may indicate muscle disease, but it is not specific to MD.

- Exercise testing may be performed, followed by a blood test to assess if elevated chemicals are produced due to poor muscle function.

- Genetic testing may be performed with a blood or saliva sample. Specific alterations in the genes that cause various forms of MD are studied for genetic mutations.

Muscle Tests

- Muscle Biopsy is the removal of a small sample of muscle withdrawn through a needle. A laboratory analysis of the muscle tissue will indicate muscular dystrophy from other muscle issues.

- Electromyography (EMG) measures the activity of muscles. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) assess the activity of nerves. In both procedures, a small needle is placed through the skin into a muscle or close to a nerve. The electrical activity of the muscle is then measured when relaxed and when it is contracted. Changes in electrical activity indicate muscle function difficulty. This test is not typically used in diagnosing Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy.

Other Diagnostic Tests that may be utilized for assessing the effects of MD

- Electrocardiography (EKG) As the heart is a muscle, in some cases, heart function is affected by MD. The EKG is an assessment of heart function. Small patches are placed on specific areas of your body to capture the heart’s beat and rhythm.

- Imaging studies, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may be used to assess muscle quality, atrophy, or other issues. Immunofluorescence utilizes a type of dye for assessment of muscle function. Other testing may include phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy and sonography for more specific concerns.

- Echocardiogram (‘Echo’) is a test using a Doppler on the outside of the body to note heart function and structure, valve function, and blood flow.

- Lung function testing is measured to assess breathing effectiveness and to assess if assisted ventilation is necessary.

Treatments

Currently, there is no cure for muscular dystrophy. However, great strides are being made to reduce symptoms and prevent further muscle damage while researchers are dedicated to finding a cure. Several options are available to manage the effects of muscular dystrophy.

Medications

Treatments are based on specific goals. The following are examples of issues that may be treated with MD.

Inflammation Glucocorticoids are steroid medications that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). These have been noted to improve muscle strength, respiratory function, and slow progression of DMD. Prednisone and deflazacort are two glucocorticoids currently prescribed. A newer glucocorticoid, vamorolone, is noted to have fewer side effects. It is for individuals two years and older. This drug is also being studied in the laboratory for individuals with Limb-Girdle MD.

Seizures A small number of individuals with MD may have seizures, particularly 7% with DMD. Antiepileptics are medications typically prescribed for individuals to control seizures. There are several antiepileptic medications available. Your healthcare provider will work with you to establish the correct choice of medication and dose.

Tone/Muscle Spasms: Low doses of antiepileptic drugs can assist with the management of muscle spasms. A lower dose can treat increased muscle tone (spasms) but seizure control will not be affected without a full dose.

Muscle Damage Immunosuppressants may assist with the delay of muscle damage in MD.

Heart Medications If MD affects heart function, the appropriate medication will be prescribed. For high blood pressure and/or heart failure, beta blockers or angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are most often used.

Surgery

Correcting issues that arise due to MD may be needed.

Orthopedic Correction of muscular contractions so joints can move freely, or scoliosis surgery to straighten the spinal vertebrae (bones), may be used to improve function and health.

Cardiac Implants, such as a pacemaker, for the improvement of heart function.

Ocular Cataract removal surgery may be needed to improve vision.

Gene Therapy

Changing a genetic defect is a challenge that is being researched. The genetic issue with MD requires treatment of a single gene, changing the way a wide series of genes function together, or modifying the entire genome of an individual. Researchers are studying genetic re-engineering in several aspects. Gene replacement therapy is being studied to replace the missing or underproduced protein. These treatments are not yet at the point of cure but are actively being studied.

A blood test is available for individuals with Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy. Genes consist of sections called exons. When an exon is missing in DMD, exon skipping helps bypass a DMD mutation(s). This is a genetic test to assess if there is an exon skipping therapy available.

Genetic treatments for DMD have been approved by the FDA. These include eteplirsen, a genetic treatment to ‘skip’ over part of the gene that is not producing the needed muscle proteins. Golodirsen, viltolarsen, casimersen, and delandistrogene moxeparvocec-rokl are others. Laboratory fetal studies are also being conducted to increase the production of dystrophin, protein instruction, and production. Ataluren is a treatment used in the European Union to affect the dystrophin gene.

Rehabilitation and Therapies

Habilitation (acquiring new skills) and rehabilitation (enhancing existing skills) can help increase an individual’s abilities. Early intervention can help maintain and preserve function, as well as prevent complications. Planning can improve independence and mobility.

Medical personnel, family members, and friends will have opinions about choices and ways to proceed. This can be overwhelming. A good way to help sort through all the information presented is to pick one healthcare professional to be the ‘captain’ of the team. Usually, this is the healthcare provider with the best comprehension of an individual’s specific health issues. Typically, it will be a specialist in the overall care and treatment of Muscular Dystrophy, such as a neuromuscular specialist, neurologist, or pediatric specialist. They will understand treatments and help you make decisions about what will be the best plan for you or your child.

Physicians, Nurse Practitioners, and Surgeons Caring for you or your child will require a team of individuals and specialists. A neuromuscular specialist who treats individuals with MD provides care specifically related to your type of MD. A general practitioner will provide support for everyday illnesses and wellness check-ups. These individuals are the foundation of the team. Other medical specialists and surgeons will be included as needed. These may include an orthopedic surgeon, cardiac specialists, a dentist, a growth and development specialist, an ophthalmologist, etc.

Nursing Specialists are available to assist with physical care and guidance. Insurance case managers are nurses who assist with obtaining equipment and supplies specifically to your needs and within your healthcare plan.

Dental Care With oral motor issues from some causes of MD, keeping moisture in the mouth and chewing issues can be challenging. Good oral care is essential in maintaining mouth and teeth health. A dentist or oral surgeon needs to understand issues of muscular dystrophy, especially in avoiding sedation such as succinylcholine and volatile anesthetics that can lead to muscle destruction and overproduction of calcium in the body. These drugs can result in heart fibrillation and even cardiac arrest if untreated. If sedation is needed, the specialist must understand the individual’s cardiac and pulmonary status. Nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents for sedation are typically used but have a longer duration in skeletal muscle. Safety monitoring is needed.

Dietary A dietitian helps ensure the right number of calories and nutrients are in the diet to maintain weight and health. In the later stages of some forms of DM, feeding through the use of a gastrostomy tube may be required for partial or full nutritional needs.

Podiatry and Skin Care Specialists Foot and skin issues can arise from shoes rubbing when an individual’s walking is altered. Sitting for extended periods can create pressure injuries. These specialists can provide prevention and adaptations to avoid, and if necessary, treat these conditions.

Respiratory Therapy As breathing can be affected by weak chest muscles and diaphragm functioning, a respiratory therapist will monitor breathing ability and provide strengthening exercises. This will help avoid and treat breathing issues, which will assist in preventing lung infections such as pneumonia. Ongoing respiratory therapy can help with coughing techniques and provide equipment to assist with breathing.

Physical Therapy will help maintain your muscle strength and provide exercises for flexibility, strength preservation, adaptive methods to perform activities of daily living, and avoid muscle contractures. Strengthening back muscles is especially important to avoid scoliosis, which can also affect your ability to breathe. Equipment can be recommended to assist with mobility. Orthotics (devices to maintain body alignment) may be recommended to improve mobility, avoid contractures, and other positioning issues.

Occupational Therapy can assist with strategies and therapies to improve function in activities of daily living such as dressing, eating, toileting, bathing, and grooming. Equipment may be recommended to assist with everyday activities.

Speech Therapy provides assistance with muscle strength if facial and throat muscles are affected by MD. These treatments may include speaking slowly, taking pauses, and use of adaptive speaking equipment. Oral motor strengthening exercises can assist with speech and eating.

Educators should be involved in establishing learning plans for children to enhance their abilities. An Individual Education Plan is provided as a joint effort between educators and parents to meet the needs of your child.

Assistive Devices Commonly used equipment used to obtain or maintain independence includes:

- Orthotics or supports for legs and feet to maintain positioning. This can also be used when extra help is needed for walking or early treatment of scoliosis. Braces, splints, and ankle foot orthotics (AFOs) are examples.

- Footwear modifications, including inserts and adaptive shoes for support, as well as easy-on and easy-off shoes.

- Mobility equipment A variety of crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs (manual and electric) can assist with mobility when needed. Positioning equipment may be needed for bed and a wheelchair may be necessary if mobility is an issue.

- Pressure dispersing equipment, medical-grade cushioning for seating and bed, will assist with pressure injury risk reduction if mobility is an issue.

- Adaptive Devices may be used for eating, speaking, toileting, and other activities of daily living. Computer-assisted devices can be used for school, play, and entertainment.

- Assisted Ventilation Breathing exercises, and the use of incentive spirometry are first-line treatments to keep respiratory muscles strong. If breathing assistance is needed, options include CPAP machines, internal and external mechanical ventilation. Use may start at night when breathing slows or around the clock.

History

The earliest description of muscular dystrophy in medical literature was in 1830 by a Scottish physician and neurologist, Charles Bell. He described a condition that led to muscle weakness in boys. Italian physicians, Giovanni Semmola and Gaetano Conte, described muscle weakness in two brothers in 1836. In 1868, Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne described the condition in a study of 13 boys. This description was the earliest version of one MD type, which became known as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). Descriptive reports continued through the years. In 1950, Peter Emil Becker described the milder form of DMD, which became known as Becker Muscular Dystrophy (BMD).

It has only been a short time since the human genome started to be unraveled. In 1987, the first MD gene was identified, the DMD gene. It was found to be on the X chromosome. Ongoing research refinements have identified DMD specifically on gene Xp21. Becker Muscular Dystrophy is also a form of mutation of the same gene. Today, there are over 30 types including subtypes of MD. As additional genetic understanding is made, more information about MD treatments is being understood.

It has only been a short time since the human genome started to be unraveled. In 1987, the first MD gene was identified, the DMD gene. It was found to be on the X chromosome. Ongoing research refinements have identified DMD specifically on gene Xp21. Becker Muscular Dystrophy is also a form of mutation of the same gene. Today, there are over 30 types including subtypes of MD. As additional genetic understanding is made, more information about MD treatments is being understood.

Corticosteroids have demonstrated prolonged muscle function and strength. These have been used since the 1970s and are still given to individuals with MD today. Newer types of corticosteroids have been developed with fewer side effects.

Research into treatments for MD has been widely studied. Electrical stimulation of nerves was attempted in the 1990s; however, it led to premature muscle degeneration. A host of drugs that affect growth and muscle function have been studied as treatments with no change in the disease.

Research into increasing dystrophin protein has not affected DMD outcomes. Several new dystrophin protein treatments are being explored. Due to advances in the study of genetics, scientists and researchers are actively pursuing treatments that will slow MD and those that eventually may cure MD.

Facts and Figures

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Duchenne/Becker (DMD/BMD)

- Affects 14 in 100,000

- Males are more affected than females

- Onset age 5 to 24 years

Myotonic (DM)

- Affects 10 in 100,000

- Males and females are equally affected

- Onset can occur at any age

Limb-Girdle (LGMD)

- Affects 2 in 100,000

- Males and Females are equally affected

- Onset can occur in childhood or adulthood

Facioscapulohumeral (FSHD)

- Affects 4 in 100,000

- Males and Females are equally affected

- Onset typically occurs in young adulthood

Congenital (CMD)

- Affects 1 in 100,000

- Males and Females are equally affected

- Onset occurs at birth or early infancy

Distal (DD)

- Affects less than 1 in 100,000

- Males and females are equally affected

- Onset occurs in adulthood

Oculopharyngeal (OPMD)

- Affects fewer than 1 in 100,000

- Males and females are equally affected

- Onset usually begins after age 40

Emery-Dreifuss (EDMD)

- Affects fewer than 1 in 100,000

- Males are more likely to be affected

- Onset usually begins in childhood

Resources

If you are looking for more information on muscular dystrophy or have a specific question, our Information Specialists are available Monday through Friday at 800-539-7309 (toll-free) or online at ChristopherReeve.org/Ask.

Additionally, the Reeve Foundation maintains a fact sheet on MD with resources. Check out our repository of fact sheets on hundreds of topics ranging from state resources to secondary complications of paralysis.

We encourage you to also reach out to muscular dystrophy organizations including:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA)

Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation (MDF)

National Institutes of Health (NIH): What Are the Treatments for MD?

Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD)

PPMD is focused on Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

References

Brais B. Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;101:181-92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-045031-5.00014-1. PMID: 21496634.

Brown SC, Muntoni F, Sewry CA. Non-Sarcolemmal Muscular Dystrophies. Brain Pathol. 2001 Apr;11(2):193-205. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00392.x. PMID: 11303795; PMCID: PMC8098386.

Butterfield RJ. Congenital Muscular Dystrophy and Congenital Myopathy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Dec;25(6):1640-1661. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000792. PMID: 31794464.

Carter JC, Sheehan DW, Prochoroff A, Birnkrant DJ. Muscular Dystrophies. Clin Chest Med. 2018 Jun;39(2):377-389. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2018.01.004. PMID: 29779596.

Cossu G, Sampaolesi M. New Therapies for Muscular Dystrophy: Cautious Optimism. Trends Mol Med. 2004 Oct;10(10):516-20. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.007. PMID: 15464452.

Dubois B. La Dystrophie Musculaire Progressive Infantile de Duchenne [Duchenne’s infantile progressive muscular dystrophy]. Lille Med. 1971 Oct;16(8):1160-77. French. PMID: 4941183.

Dubowitz V. Congenital Muscular Dystrophy: An Expanding Clinical Syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2000 Feb;47(2):143-4. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200002)47:2<143:aid-ana2>3.0.co;2-y. Erratum in: Ann Neurol 2000 Apr;47(4):554. PMID: 10665483.

Edwards RH. Management of Muscular Dystrophy in Adults. Br Med Bull. 1989 Jul;45(3):802-18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072359. PMID: 2688830.

Emery AE. The Muscular Dystrophies. Lancet. 2002 Feb 23;359(9307):687-95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. PMID: 11879882.

Emery AE. Muscular Dystrophy into the New Millennium. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002 May;12(4):343-9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00303-0. PMID: 12062251.

Emery AE. Some Unanswered Questions in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1994 Jul;4(4):301-3. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)90065-5. PMID: 7981586.

Engvall E, Wewer UM. The New Frontier in Muscular Dystrophy Research: Booster Genes. FASEB J. 2003 Sep;17(12):1579-84. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1215rev. PMID: 12958164.

Evans BK, Goyne C. Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy: Review and Recent Scientific Findings. Am J Med Sci. 1991 Aug;302(2):118-23. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199108000-00010. PMID: 1897557.

Falsaperla R, Praticò AD, Ruggieri M, Parano E, Rizzo R, Corsello G, Vitaliti G, Pavone P. Congenital Muscular Dystrophy: From Muscle to Brain. Ital J Pediatr. 2016 Aug 31;42(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0289-9. PMID: 27576556; PMCID: PMC5006267.

Heydemann A, Doherty KR, McNally EM. Genetic Modifiers of Muscular Dystrophy: Implications for Therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 Feb;1772(2):216-28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.013. Epub 2006 Jul 11. PMID: 16916601.

Hoang T, Dowdy RAE. A Review of Muscular Dystrophies. Anesth Prog. 2024 May 3;71(1):44-52. doi: 10.2344/673191. PMID: 39503119; PMCID: PMC11101287.

Hoffman EP. Muscular Dystrophy: Identification and Use of Genes for Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999 Nov;123(11):1050-2. doi: 10.5858/1999-123-1050-MD. PMID: 10539906.

Hsu YD. Muscular Dystrophy: From Pathogenesis to Strategy. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2004 Jun;13(2):50-8. PMID: 15478675.

Johnson NE. Myotonic Muscular Dystrophies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Dec;25(6):1682-1695. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000793. PMID: 31794466.

Kanagawa M. Dystroglycanopathy: From Elucidation of Molecular and Pathological Mechanisms to Development of Treatment Methods. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Dec 6;22(23):13162. doi: 10.3390/ijms222313162. PMID: 34884967; PMCID: PMC8658603.

Karthikeyan P, Kumar SH, Khanna-Gupta A, Bremadesam Raman L. In a Cohort of 961 Clinically Suspected Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patients, 105 Were Diagnosed to Have Other Muscular Dystrophies (OMDs), with LGMD2E (variant SGCB c.544A>C) Being the Most Common. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2024 Nov;12(11):e2123. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.2123. PMID: 39548682; PMCID: PMC11568062.

Kunkel LM, Hoffman EP. Duchenne/Becker Muscular Dystrophy: A Short Overview of the Gene, the Protein, and Current Diagnostics. Br Med Bull. 1989 Jul;45(3):630-43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072349. PMID: 2688821.

Lim KRQ, Yokota T. Current Strategies of Muscular Dystrophy Therapeutics: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2587:3-30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2772-3_1. PMID: 36401021.

Malik HZ, Sharma G, Moreno C, Parcha SP. A Medley of Malnutrition and Myotonic Dystrophy: Twice Unlucky. Cureus. 2022 Jan 12;14(1):e21180. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21180. PMID: 35165628; PMCID: PMC8837520.adult

Mathews KD. Muscular Dystrophy Overview: Genetics and Diagnosis. Neurol Clin. 2003 Nov;21(4):795-816. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(03)00065-3. PMID: 14743650.

Mathews KD, Moore SA. Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003 Jan;3(1):78-85. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0042-9. PMID: 12507416.

Matsuo M. Duchenne/Becker Muscular Dystrophy: From Molecular Diagnosis to Gene Therapy. Brain Dev. 1996 May-Jun;18(3):167-72. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(96)00007-1. PMID: 8836495.

Morris P. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Challenge for the Anaesthetist. Paediatr Anaesth. 1997;7(1):1-4. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1997.d01-41.x. PMID: 9041567.

Mul K. Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2022 Dec 1;28(6):1735-1751. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001155. PMID: 36537978.

Murphy ME, Kehrer JP. Oxidative Stress and Muscular Dystrophy. Chem Biol Interact. 1989;69(2-3):101-73. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90075-6. PMID: 2649259.

Nakashima M, Suga N, Yoshikawa S, Matsuda S. Caveolin and NOS in the Development of Muscular Dystrophy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Aug 12;25(16):8771. doi: 10.3390/ijms25168771. PMID: 39201459; PMCID: PMC11354531.

Nonaka I. Distal Myopathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999 Oct;12(5):493-9. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199910000-00002. PMID: 10590885.

Nonaka I, Kobayashi O, Osari S. Nondystrophinopathic Muscular Dystrophies Including Myotonic Dystrophy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996 Jun;3(2):110-21. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(96)80040-4. PMID: 8795845.

Orrell RW. Diagnosing and Managing Muscular Dystrophy. Practitioner. 2012 Sep;256(1754):21-4, 2-3. PMID: 23252132.

Phylactou LA. Special Issue–Towards Understanding the Mechanisms and Curing of Muscular Dystrophy Diseases. Molecules. 2015 Jul 16;20(7):12944-5. doi: 10.3390/molecules200712944. PMID: 26791289; PMCID: PMC6332128.

Rowland LP, Fetell M, Olarte M, Hays A, Singh N, Wanat FE. Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 1979 Feb;5(2):111-7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410050203. PMID: 426473.

Russo C, Surdo S, Valle MS, Malaguarnera L. The Gut Microbiota Involvement in the Panorama of Muscular Dystrophy Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Oct 21;25(20):11310. doi: 10.3390/ijms252011310. PMID: 39457092; PMCID: PMC11508360.

Saito K. Prenatal Diagnosis of Fukuyama Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Prenat Diagn. 2006 May;26(5):415-7. doi: 10.1002/pd.1426. PMID: 16570239.

Savarese M, Sarparanta J, Vihola A, Jonson PH, Johari M, Rusanen S, Hackman P, Udd B. Panorama of the Distal Myopathies. Acta Myol. 2020 Dec 1;39(4):245-265. doi: 10.36185/2532-1900-028. PMID: 33458580; PMCID: PMC7783427.

Siegel IM. Muscular Dystrophy: Multidisciplinary Approach to Management. Postgrad Med. 1981 Feb;69(2):124-8, 131-3. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1981.11715679. PMID: 7454643.

Tay JS, Lai PS, Low PS, Lee WL, Gan GC. Pathogenesis of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: the Calcium Hypothesis Revisited. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992 Aug;28(4):291-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02669.x. PMID: 1497954.

Tihaya MS, Mul K, Balog J, de Greef JC, Tapscott SJ, Tawil R, Statland JM, van der Maarel SM. Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy: The Road to Targeted Therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023 Feb;19(2):91-108. doi: 10.1038/s41582-022-00762-2. Epub 2023 Jan 10. PMID: 36627512; PMCID: PMC11578282.

Udd B. Distal Muscular Dystrophies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;101:239-62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-045031-5.00016-5. PMID: 21496636.

Wood CL, Straub V. Bones and Muscular Dystrophies: What Do We Know? Curr Opin Neurol. 2018 Oct;31(5):583-591. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000603. PMID: 30080716.

Yamauchi H, Sobue K. [Anesthesia Preoperative Preparation of Muscular Dystrophy]. Masui. 2010 Sep;59(9):1093-5. Japanese. PMID: 20857662.

Yamashita S. Recent Progress in Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy. J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 29;10(7):1375. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071375. PMID: 33805441; PMCID: PMC8036457.

Zingariello CD, Mohamed Y, Jorand-Fletcher M, Wymer J, Kang PB, Rasmussen SA. Diagnoses of Muscular Dystrophy in a Veterans Health System. Muscle Nerve. 2024 Aug;70(2):273-278. doi: 10.1002/mus.28112. Epub 2024 May 23. PMID: 38783566.